FOCUS

#21

Video games : a ‘no woman’s’ land ?

Written in association with Women in Games France, an organization created in 2017 who work for gender diversity in the video game industry in France. Its aim is to double the number of women and non-binary people in the industry within the next ten years.

Overview : While video games have long been considered a “no woman’s land”, marketed as a toy for boys and a breeding ground for outright sexism, the industry is slowly but surely evolving towards greater representation of female gamers, characters and industry professionals.

At the helm : the impossible mix ?

The video game industry is the largest industry the world – surpassing music and cinema. In France, the industry includes 1,200 companies and employed nearly 12,000 people, in 2018. Only 22% were women – and this percentage drops to 6% in technical professions and 11% in management positions.

Yet it was a woman, Ada Lovelace, who wrote the first ever computer programme in history, even before the arrival of the modern computer. Until the 1950s, despite being considered unskilled, this field was reserved for women.

The advent of Microsoft and Apple in the 1980s changed all of that. The success of their products created such a craze that some aspiring computer scientists abandoned hardware engineering in favour of software development. Men’s attraction to these more highly valued professions led to a decline in female software developers. In 1984, 37% of American computer science students were women, a peak that will never be reached again.

This phenomenon correlates to the reality that discourages women from pursuing a career in the software industry. A report published in June 2022, by the international trade union federation Uni Global, reveals that 35% of employees in the sector have already been victims of sexual harassment. The companies concerned have responded by various measures: dismissals, sanctions, top management reviews, appointment of diversity and inclusion officers, preventive actions, etc. The next few years will provide an opportunity to assess the relevance and impact of these measures.

Ada Lovelace, first female programmer

These problems also exist in video games, as demonstrated by the “Don’t change your name, change the game” campaign: when gamers adopt female pseudonyms, they are immediately harassed. Despite this, the figures have been clear for several years: one out of every two players is a woman. So the statistics are moving in the right direction, but there’s still a long way to go before women are fully represented in the video games industry, both in front and behind the screen. By encouraging diversity in the studios, on-screen representations will be more authentic and respectful, attracting new female consumers… who may well want to join the ranks of video game professionals. The challenge lies in creating this virtuous dynamic.

From trophy to heroine,

the history of the female character

When the first humanoid heroes saw the light of day, the video game industry was driven by the belief that content were to be designed by men, for men. They favoured male characters such as Mario, Donkey Kong and BJ Blaskowitz. While there are a few playable female characters, they are often trophy wives, narrative pretexts and rewards for the male hero.

Yet the first video game consoles and platforms were not gendered: arcade terminals were installed in public places, and games like Pacman or Space Invaders were not targeted specifically at a male audience. But in the 1980s, video games began to be marketed as a product for boys: the release of Nintendo’s “Game Boy” in 1989 confirmed this perception.

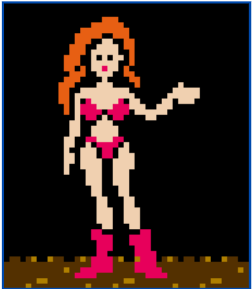

As graphics improved, female characters became objects of desire: their shapes, hair and faces were emphasised for the purpose of seduction. This was the era of hypersexualisation. In Metroid (1986), for example, the character of Samus Aran is covered in thick armour that conceals her gender throughout the game’s various stages. But once the player has won, she is revealed (literally and figuratively) as a reward for her performance. The quicker the game is over, the more she’s stripped down, to the point of appearing in a bikini. She goes from being a character with qualities normally attributed to male heroes (strength, courage…) to an image to be contemplated, given as a reward. She is reduced to her body; at first an active subject, she is now nothing more than a desired object. Yet heroines can also be very popular in the world of video games: the Netflix series Arcane, based on the game League of Legends, has been a great success with viewers, even though it is centred around two of the game’s female characters.

Samus Aran at the end of the first Metroid game

Initiatives to promote better representation

Leading figures from a wide range of backgrounds have committed themselves to making the video games industry more inclusive, with Anita Sarkeesian, founder of the NGO Feminist Frequency, Adrienne Shaw, an academic specialising in issues of representation, and Aderyn Thompson, influencer and consultant on diversity and disability for Ubisoft, among the most influential.

Numerous organisations, associations and groups are also working for greater gender diversity. For example, Stream’Her is a community that supports and promotes women in the world of streaming; Afrogameuses campaigns for better representation of racial minorities; Witchgamez raises awareness of sexism in video games. The “Representing diversity” guide has been published by the Game Impact collective, serving as a guide for professional designers who want to design characters in a more diverse and respectful way, in terms of gender, ethnicity, and raising awareness of marginilized identities.

These actions are essential because by diversifying their creative teams, companies tend to produce content that is more accurate, richer and more nuanced, enabling them to reach a less homogenous target (whether that target is made up of women, but also racialised or LGBTQ+ people), who will be more inclined to join an industry that considers them and inspires them.

For its part, Women in Games France is deploying its actions through three pillars: informing women about the professions and opportunities in the industry, supporting their development of up and coming female professionals, and raising awareness among of the benefits of gender diversity in video games.

Tyler, transgender character from Tell Me Why

Among its initiatives, the association has developed an eSport incubator to help female players join the competitive scene. In fact, only 7% of female eSports players play amateur games with rankings and competitions. The 2021-2022 season, in partnership with Riot Games (League of Legends, Valorant) and Ubisoft (Rainbow 6: Siege), supported players by providing competitor coaching, meeting professionals, and granting access to international competitions. The documentary Legend(e)s, available on Youtube, tells the story of two competitive French female eSport gamers

Légend(e)s, the documentary

It is a joint effort between associations, groups, governments and companies that will make it possible to improve the representation of women in video games in a concrete and lasting way. Whether women are in front of or behind the screen, in order to have the full potential of the world’s leading cultural industry, everyone must be represented.

The Observatoire des images, created in 2021, is the first associative body to bring together all those interested in the role of images in cinema, television, video games and advertising, particularly on the Internet. Convinced that images can freeze representations and lock people into stereotypes, or on the contrary enable emancipation and open up the field of possibilities, the observatory’s partners have come together to reflect and act together, whether their members work in production, distribution, funding, communication, research, institutions, etc.

The coalition’s objectives include: raising awareness among public authorities, professionals and the general public; developing research into the reception of images and highlighting existing work; pooling and supporting professional practices; promoting projects and teams committed to combating stereotypes.

Join us : observatoiredesimages.org

Rejoignez-nous : observatoiredesimages.org