FOCUS

#23

Nature’s anger : climate fiction and ecological perspective

By Sophie Suma, PhD in Visual Arts, lecturer and researcher in Visual Studies and Cultural History at the National Institute of Applied Sciences of Strasbourg and the Faculty of Arts at the University of Strasbourg. Her research focuses on visual ecologies and the representation of identities and environments in the media, particularly in television series’.

She coordinates the Visual Cultures research group (Accra – UR 3402), which explores images and visual knowledge, and the webrevue archifictions.org, focusing on fiction studies.

Overview : At a time when environmental issues are at the heart of contemporary concerns, audiovisual fiction dealing with ecology continues to captivate audiences. Since the 1970s, a number of environmental and ecological films and series have taken nature as their subject. By romanticising certain scientific theories and portraying animist and holistic representations, some of these dramas personify and anthropomorphistic nature to put humans to the test in a perpetual conflict: what are our consequences?

From the late 1950s onwards, ecological and environmental issues came to the fore on the screen. Films such as Wind Across the Everglades (1959) heralded a genre of audiovisual fiction that raised awareness of the need to preserve nature (aka the environment, aka the Earth). So-called “environmentalist” preventive fictions such as The Emerald Forest (1985), Gorillas in the Mist: The Story of Dian Fossey (1988), or The Pelican Brief (1993) became real references. They echo texts published from the 1960s onwards, such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), in which the author links the disappearance of certain birds to the intensive use of pesticides. The genre continues and develops in recent series such as Chernobyl (2019), or The 100 (2014- 2020), which evoke nuclear disasters, or the Brazilian telenovelas Aruanas (2019+) and Frontera verde (2019), which encourage the preservation of the Amazon rainforest. But what do these kinds of audiovisual productions tell us more concretely about our relationship with ecology?

HUMAN PUT TO THE TEST BY NATURE

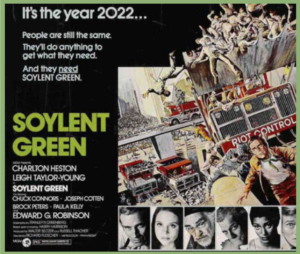

These films include: No Blade of Grass (1970), Soylent Green (1974), Waterworld (1995), The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and 2012 (2009). In series’ like Snowpiercer (2020+), Incorporated (2016-2017), Als de Dijken Breken (2016), Wielka Woda (2022), and The Last of Us (2023), humans are the victims of natural and health disasters caused by a series of disturbances caused by the impact of our industries on environmental ecosystems. Christian Chelebourg talks of eco-fiction, Frédéric Neyrat of eco-apocalyptic cinema.

Soylent Green, Richard Fleischer (1974)

But in this range of productions in which nature puts humans to the test, an even more singular sub-genre of fiction appeared in the 1970s. In these films and series’, nature is presented as thinking, autonomous and conscious, and develops autonomous defensive strategies. The scripts place particular emphasis on nature’s intelligence. The audience is made aware of the power of a particular territory, endemic species or natural element. In Phase IV (1974), Saul Bass depicted killer ants in the Arizona desert. In Long Weekend (1978, and its 2008 remake), nature in the Australian Bush is organised to scare away the couple of intrusive holidaymakers. In the film The Happening (2008), the wind drives humans to suicide by carrying a strange toxin. In the series The Rain (2018), men and women are killed by a mysterious toxic rain. Beyond an aesthetic designed to shock and sometimes surprise with its disturbing realism, these images of nature in a rage echo the ecological visions emanating from a number of scientific theories that seem to have infused the media and audiovisual fictions for several decades.

The last wave, a romanticisation of the Gaia Hypothesis

Poster of The Last Wave (2019)

In the mini-series The Last Wave (2019) by Raphaëlle Roudaut and Alexis Le Sec, an ominous cloud appears over the fictional commune of Brizan, located in the French Landes region. Shortly afterwards, eleven surfers mysteriously disappear at sea during a competition. When they reappear, they are endowed with strange powers and have apocalyptic visions.

In the days that follow, a number of worrying geological and health phenomenons appear in the city. The premise of The Last Wave is to present a force of nature (embodied by a cloud) that thinks and organises itself to attack humans, because it can no longer tolerate their selfishness. Like the animals and plants in Phase IV and Long Weekend, or the wind and rain in The Happening and The Rain, here nature defends itself, taking revenge, and teaches humanity a lesson by responding with climatic and health disasters.

Extract from the series The Rain (2018-2020)

But since it has intentions and acts like a living organism in punishing the inhabitants of Brizan, the cloud is not just an aesthetic representation of a natural phenomenon. This choice can be seen as a romantic interpretation of the Gaia Hypothesis proposed in the 1960s-70s by the English climatologist James Lovelock, in which the Earth is defined as a “superorganism”. However, by using this term, Lovelock does not consider the planet as a living, thinking organism, but as a product, in constant transformation, of all the entities that live on it – from termites, to forests, to humans. Accompanied by microbiologist Lynn Margulis, Lovelock demonstrates that the products of engineering, i.e. everything that humans, and non-humans build or produce, are part of the evolution and metamorphosis of the earth’s environments. We need to realise that all these phenomenons have consequences for our environment. The Earth, humans and non-humans – actors in what Bruno Latour calls the collective – are therefore interdependent. According to Latour, it is a widespread misunderstanding to think that the Gaia Hypothesis equates the Earth with a living organism.

The personification of nature, between fiction and ecological narratives

The Brizan inhabitants’ experience of the cloud recalls various theoretical and historical accounts in which the Earth is personified. Whether it’s the animist experiences studied by Philippe Descola, or the representations described by Carolyn Merchant and found in the history of the natural sciences since Antiquity, many images depict a conscious nature endowed with intentions: a protective and nurturing mother, a force to be feared, an organic entity, and so on. When the cloud chooses to condemn the local population to death as punishment, it is not just exercising divine power, it is behaving like a human being. As Teresa Castro might suggest, the script of The Last Wave reflects an animism that anthropomorphises the cloud. Here, Nature’s wrath refers to guilt and catharsis, revealing the anguish generated by the perverse effects of technology and the human technologies of the modern world.

Humans and nature are portrayed in a permanent conflict that values vengeance and domination. In the final episode of The Last Wave, the surfers thwart the cloud’s destructive plans by communicating together, but they are not working in unison with it, but against it. Their efforts become in vain, as the cloud later reappears in other parts of the world, clearly with the same vengeful intentions.

Even if these ecologist fictions fantasize the growth of animist and holistic thinking which would aim to pacify these conflicting relationships, they are more of a reflection of a very conventional naturalist representation which re-enacts the historical division between nature and culture by pitting humans against a personified nature that is no longer very ‘natural’.

The cloud that embodies Nature in The Last Wave

Unfortunately, this contradiction prevents us from imagining other ways of representing the ecological thinking discussed by Lovelock, Margulis, Latour and others before them. As Cyril Dion and Mélanie Laurent suggest in their documentary film Demain (2015), we are still waiting for this kind of audiovisual fiction to be more positive. Couldn’t they then show us another representation of the possible relationship between humans and nature, another ecological vision that would emphasise cooperation, proposing a more symbiotic world, less alienating, and where animism and holism would perhaps take on more meaning? The proposal made by the American Ernest Callenbach in 1975 in his novel Ecotopia, which remains undeveloped, is perhaps a serious avenue in this respect. The appearance of the “Cinema for Climate” category at the Cannes Film Festival in 2021 will perhaps play a role in the emergence of alternative imaginaries…

The Observatoire des images, created in 2021, is the first associative body to bring together all those interested in the role of images in cinema, television, video games and advertising, particularly on the Internet.

The coalition’s objectives include: raising awareness among public authorities, professionals and the general public; developing research into the reception of images and highlighting existing work; pooling and supporting professional practices; promoting projects and teams committed to combating stereotypes.

Join us : observatoiredesimages.org