FOCUS

#08

Women and tech: 404 error on the screen?

With Women & Girls in Tech, a coalition launched in 2019 by BNP Paribas, Digital Ladies & Allies and Simplon to develop the representation of women in the digital sector through intergenerational content and events. — Find out more: https://wogi.tech/

Summary: While women represent a minority but not negligible share of the professionals working in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics sectors, they are often left out of the technological picture. There is a fine line between content that reinforces gender stereotypes and the masculine figure of the geek. However, models do exist and initiatives to break out of clichés show that it is possible to intervene to raise awareness both in the production and distribution chain and among the general public.

Worldwide, 24% of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) jobs are held by women, who design 22% of algorithms, hold 11% of cybersecurity positions and 16.9% of board seats. While almost 25% of services and technological devices we use have been developed by women, the hero who appears on the screen behind a computer or in a laboratory has long been a white man, whether in films (Kenneth Johnson’s Call Me Johnny 5, 1985), television series (Robert K. Weiss’ Code Lisa, 1994), or cartoons (Gary in Matt Groening’s The Simpsons, since 1989). Even today, women on screen are often left out of the technological picture.

CONTENT THAT REINFORCES GENDER STEREOTYPES

In Belgium, only 44% of the main roles in fiction are played by women, and 60% of the roles played are associated with being a mother. Only 33% of UK children’s content involves women in a scientific role. Instead of giving greater visibility to women in science, the content on the screens actually tends to widen the gap between men and women.

Many inventions in the fields of computer science or mechanics are made by women that do not receive, however, the same credit and attention as their male counterparts. Although the rate of women experts on television and radio continues to increase, with 41% of all invited experts in 2020, women are still not represented in our visual and popular culture as a force of innovation or creation. This entrenches a double perverse dynamic: audiovisual content reflects inequalities, without proposing female role models who could be vectors of change. Worse still, this content maintains and reinforces gender stereotypes.

The Austrian sociologist Eva Flicker has identified seven stereotypical figures of the female scientist that are often found in popular audiovisual content: the “spinster”, the tough woman who liberates other women, the slightly naive expert, the evil plotter, the scientist’s daughter or assistant, the lonely heroine and the very trendy “malignant digital beauty”, which reflects the growing popularity of the hacker/developer.

Women associated with technology are thus:

- often portrayed as passive, technologically illiterate assistants supporting their heroic bosses; the scientist being generally a man, unlike his secretary or lab assistant. On television, scientific discourse is often monopolised by men. For example, in France, during the so-called COVID crisis, women represented only 27% of doctors and 40% of pharmacists interviewed, while they represent 46% and 60% of these professions respectively;

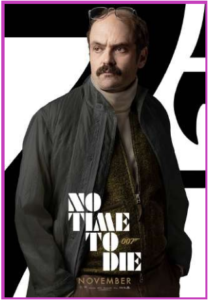

- more often naked and sexualised than male characters associated with technology (31.5% are presented as attractive compared to 15.2% for men); for example, in James Bond, nuclear physicist Christmas Jones, played by Denise Richards (The World is Not Enough directed by Michael Apted, 1999), versus missing scientist Valdo Obruchev, played by actor David Dencik (No Time to Die directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga, 2021).

The male scientist in James Bond:

Valdo Obruchev, No time to die, 2021

They are regularly cast in the role of “femme fatale” who must necessarily use their charms rather than their intellectual faculties to get what they want. Men are not subject to these aesthetic constraints and are free to be ugly or even grotesque, since it is their expertise that justifies their relevance in the narrative;

La scientifique femme dans James Bond :

Christmas Jones, Le monde ne suffit pas, 1999

- linked to a man, who manipulates or influences them and to whom they owe their technical abilities. In Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014), the two main female characters, Dr. Amelia Brand (Anne Hathaway) and Murphy Cooper (Jessica Chastain) only practice their professions in the eyes of their respective father figures;

- caught up in their emotions: as is the case with Jules Ostin, played by Anne Hathaway, in Nancy Meyers’ The Intern (2015), an entrepreneur in the tech start-up world whose ability to conduct her business is undermined by her love and family history;

- awkward and clumsy: in the cartoon Scooby-Doo (since 1969), Velma, who is the smartest character in the group of friends, is often the object of humorous comments that ridicule her. Single, she is characterised by physical features that do not correspond to the usual beauty criteria, and is constantly caught up in slightly crazy scenes. In contrast, Daphne, who is drawn according to conventional standards of beauty and is in a love affair with Fred, the male character portrayed as attractive, appears on screen more often even though it’s usually Velma’s ingenuity that gets the group out of trouble.

Daphné , Scooby-Doo

Vera , Scooby-Doo

THE GEEK-WOMAN WAS A MAN

At the same time, when a film or series organises its narrative arc substantially around a female character involved in scientific or technological activities, it is not uncommon for her representation to borrow many male characteristics:

- Lisbeth Salander, played by Noomi Rapace in Niels Arden Oplev’s Millenium (2009), fits into all the codes of representation of the “geek” figure. Her character is based on a succession of stereotypes that actively constitute her as a marginal character. Her physical appearance is very androgynous, her clothes, hair and make-up are deliberately offbeat and disturbing, while her attitude is generally hostile and taciturn;

- Chloe O’Brian, played by Mary Lynn Rajskub in Joel Surnow and Robert Cochran’s 24 (2001-2014), is the computer specialist for the anti-terrorist unit. The computer genius also fits the pattern of a brilliant but moody, irascible and obsessive femininity, and puts the success of the missions entrusted to her before her emotions, at the risk of remaining very isolated and without a social life;

- Rebecca Webb, played by Hannah Ware, in Howard Overman’s UK series The One (2021) is the woman who developed the fictional application of the topic. She’s a brilliant scientist and the head of a science and technology empire. Depicted as ‘strong’ and ruthless, she masters and crushes all obstacles in her path and does not hesitate to use cruelty to achieve her ends. She values success and knowledge over love, and thus assumes the characteristics usually attributed to the male gender.

However, the images conveyed by screens shape our imaginations and have concrete repercussions on women’s ability to project themselves in the STEM sector. All the images, whether fictional or not, are part of the project of constructing a reality by their creators. For minorities or women, the choices related to their visibility and its features are not trivial.

Their representation in cinema, television, advertising or video games is politically charged, as it sets and determines the relationship with the rest of society. Screens can therefore help to reduce stereotypes and open up imaginations.

MINORITY MODELS TO BE HIGHLIGHTED

Some works of fiction, many of them very successful, break the codes and offer alternatives, showing women:

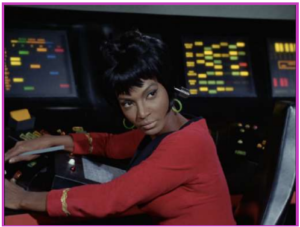

- with high responsibility and scientific expertise. In the world of fiction, for example, Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek (from 1966) features Nyota Uhura, played by Nichelle Nichols, as one of the first major roles for a black woman. Her presence on board the Enterprise NCC-1701 as a lieutenant, more senior than some of the male crew, is thus highly symbolic. More recently, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther (2018) features the character of Shuri, played by Letitia Wright, who breaks the stereotypes associated with the portrayal of female scientists and offers a portrait of a contrasting and brilliant femininity without stereotypes. In the world of series, 3615 Monique directed by Emmanuel Poulain-Arnaud and Armand Robin (2020) features the character of Stéphanie, played by Noémie Schmidt, as the head of the team of men in charge of the development of the digital messaging service that she has the idea of launching. Independent and strong in business, she establishes herself as the authority figure of the group in the face of awkward and dissipated male figures;

- combative and courageous: like the spies in the cartoon, Totally Spies by Vincent Chalvon-Demersay and David Michel (2002 to 2013). These characters paved the way for a gradual diversification of female identities in youth programmes in the early 2000s;

- more seasoned than their male counterparts: for example, in Robert Zemeckis’ science fiction film Contact (1997), Jodie Foster is the only one who imagines she can develop communication with alien life, while in Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion (2011), Kate Winslet is a whistleblower who warns of the seriousness of a pandemic that everyone is playing down. These two characters play an essential role in the narratives and the resolution of the plots.

Lieutenant Nyota Uhura (Nichelle Nichols),

Star Trek

PROJECTS TO BE DEVELOPED FOR DE-INVISIBILISATION

Many female STEM figures are still missing from the screen: biopics are to be written, stories are to be drawn. Workshops and script bursaries could be launched so that some of them finally appear on the screen. There is no excuse: they exist and their lives already sound like big budget movies! They include, the American Tabitha Babbitt, who became a member of the Shakers in the Harvard community, invented the circular saw, the spinning wheel head and the dental prosthesis in the 18th century; the Englishwoman Josephine Cochrane, who invented the dishwasher in 1886; Mary Anderson, an American, who designed windscreen wipers in 1903 (while at the same time a law in force in certain American states only allowed women to drive on condition that their husbands ran in front of the vehicle waving a flag, warning of the danger); Grace Hopper, Vice Admiral of the US Army, who conceived and programmed the first compiler for computer languages (COBOL language) in 1952. Such personalities deserve to be highlighted, in order to show the diversity and complexity of the profiles of women scientists and inventors.

Already, initiatives are helping to change the way people think. This is the case of the Femmes et Cinéma association, which each year with France Télévisions, via its “Femmes actives” programme, supports short film projects featuring women in the world of work and organises round tables and conferences in schools, to raise awareness among the youth.

Similarly, Impact Film co-produces fiction and feature films featuring independent women characters, including in its editorial line those who are active in the science and technology sector. At the same time, the Franco-Swiss foundation Womanity has been developing since 2007 the Girls can Code programme, particularly in Afghanistan, which has enabled 34,200 young girls and 1,100 teachers to be trained in computer programming, an, audiovisual programmes for an Arab audience featuring young women. This is helping to deconstruct clichés and stereotypes.

In order to consolidate this dynamic, there is still work to be done to raise awareness of the entire audiovisual content production chain: financing, production, distribution, etc…

Shuri (Letitia Wright), Black Panther

L’Observatoire des images, created in 2021, is the first associative body to bring together those who are interested in the influence of representations in cinema, television, video games and advertisements, especially on the Internet.

Convinced that images can freeze representations and lock them into stereotypes or, on the contrary, enable emancipation and open up infinite possibilities, the partners of the observatory – whose members are working in production, distribution, financing, communication, research, institutions, etc. – organised meetings in order to reflect and act together.

The objectives of the coalition include:

– raising awareness of the public authorities, professionals and the public;

– developing research on the reception of images and highlight existing work;

– aggregating and supporting professional practices;

– promoting projects and teams concerned with combating stereotypes.

— Join us: observatoiredesimages.org !